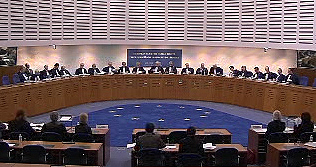

Before the Grand Chamber

Molli Sali v. Greece (no. 20452/14) – Grand Chamber Judgment 19 December 2018. The case concerned the application by the Greek courts of Islamic religious (Sharia) law to a dispute concerning inheritance rights over the estate of the late husband of Ms Molla Sali, a Greek national belonging to the country’s Muslim minority. The Court’s First Section relinquished jurisdiction to the Grand Chamber on 8 June 2017. The Grand Chamber heard arguments in the case on 6 December 2017, and while judgment was awaited, on 9 January 2018 the Greek Parliament voted to limit the powers of Islamic courts operating in Thrace, home about 100,000 Muslims. In its judgment of 19 December 2018, the Grand Chamber found a violation of Article 14 (prohibition of discrimination), read in conjunction with Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 (protection of property). In particular, “the difference in treatment suffered by Ms Molla Sali as the beneficiary of a will drawn up under the Civil Code by a Greek testator of Muslim faith, as compared with a beneficiary of a will drawn up under the Civil Code by a Greek testator not of Muslim faith, had not been objectively and reasonably justified.

Kàroly Nagy v. Hungary (no. 56665/09) – Grand Chamber Judgment 14 September 2017. Kàroly Nagy, a pastor in the Hungarian Calvinist Church, was dismissed following a disciplinary procedure in 2006. He initiated labor-law proceedings for unpaid renumeration against the church, but complained that his case was dismissed by state courts because they are ecclesiastical in nature. Mr Nagy then brought proceedings before both the labour and civil courts. Both sets of proceedings were ultimately discontinued on the ground that the courts had no jurisdiction. The labour courts discontinued the proceedings in December 2006, on the ground that the dispute concerned Mr Nagy’s service as a pastor and therefore the provisions of Labour Law were not applicable in his case. That decision was upheld on appeal in April 2007. Mr Nagy’s civil-law claim was also ultimately discontinued in May 2009, the Supreme Court concluding that there was no contractual relationship between Mr Nagy and the Calvinist Church, and therefore his claim had no basis in civil law. Mr Nagy complained about the Hungarian courts’ refusal to hear his claim for compensation on the merits, alleging that he had been denied access to a court merely on account of his position as a Calvinist pastor. He relied in particular on Article 6 § 1 (access to court). In its judgment of 1 December 2015, the Second Section found in a 6-3 decision no violation of Article 6 § 1. {Some text from the press release of the Registrar of the Court.}

Finding the reasoning of the majority “disturbing”, Judges Sajó, Vučinić, and Kūris issued a lengthy joint dissenting opinion.

Accepting the applicant’s request to hear the case, the Grand Chamber on 14 September 2017 issued a ruling holding, by ten votes to seven, that in view of the overall legal framework in Hungary, Mr Nagy had no “right” which could be said, at least on arguable grounds, to be recognised under domestic law. Article 6 (right of access to a court) was therefore not applicable in the present case, which must be found to be inadmissible.

From the Court’s press release: “The Court noted that in the applicant’s case all the national courts had discontinued the proceedings holding that Mr Nagy’s claim could not be enforced in national courts since his pastoral service and the letter of appointment on which it was based had been governed by ecclesiastical rather than the State law. Furthermore, these findings were in line with the principles laid down by the Constitutional Court in its decision 32/2003 of 2003, concerning the issue of access to court of persons employed by religious organisations.

“Having regard to the nature of Mr Nagy’s complaint, to the basis on which he had served as a pastor, and to domestic law as interpreted by the domestic courts, the Court could not but conclude that Mr Nagy had no ‘right’ which could be said, at least on arguable grounds, to be recognised under domestic law.”

Judge Sicilianos expressed a dissenting opinion; Judges Sajó, López Guerra, Tsotsoria and Laffranque* expressed a joint dissenting opinion; Judge Pinto de Albuquerque and Judge Pejchal each expressed a dissenting opinion. These opinions are annexed to the judgment.

*From the dissent of Judges Sajó, López Guerra, Tsotsoria and Laffranque: “In the present case the majority have concluded that the applicant pastor’s pecuniary claims, which were indirectly related to his ecclesiastical service, did not constitute a civil right under domestic law. Given the absence of a civil right, the majority asserted that there could be no issue of access to justice. We respectfully dissent. Such an understanding of the case-law not only encourages domestic arbitrariness, but may also deprive many people who enter into ecclesiastical service of the protection of due process. Ultimately, this judgment risks endorsing the position that all appointments and service agreements formed with religious institutions that are subject to internal rules fall outside the jurisdiction of the State. Consequently, such agreements are rendered unreviewable and any rights are unenforceable under domestic law.”

Medžlis Islamske Zajednice Brčko and Others v. Bosnia and Herzegovina (no. 17224/11) – Grand Chamber Judgment 27 June 2017. Applicants (four organizations) complained of violation of freedom of expression in the order to pay damages for defamation following publication of a letter written to the highest authorities of their district complaining about a person’s application for the post of director of Brčko District’s multi-ethnic radio and television station. The Court found that four statements in the letter contained allegations portraying the candidate in question (Ms M.S.) as a person who was disrespectful and contemptuous in her opinions and sentiments about Muslims and ethnic Bosniacs. The nature of the accusations had been such as to seriously call into question Ms M.S.’s suitability for the post of director of the radio and her role as editor of the entertainment programme of a multi-ethnic public radio station. However, the applicants had not established before the domestic courts the “truthfulness of these statements which they knew or ought to have known were false” despite being bound by the requirement to verify the veracity of their allegations even if these had been disclosed to the authorities by means of private correspondence. The Court therefore held that the applicants had not had a sufficient factual basis to support their allegations and that the interference with their freedom of expression had been supported by relevant and sufficient reasons and had been proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued (protection of Ms M.S.’s reputation). The Court also held that the domestic authorities had struck a fair balance between the applicants’ freedom of expression and Ms M.S.’s interest in the protection of her reputation, thus acting within their margin of appreciation.

Paradiso and Campanelli v. Italy (no. 25358/12) – Grand Chamber Judgment 24 January 2017. The case concerned the placement in social-service care of a nine-month-old child who had been born in Russia following a gestational surrogacy contract entered into by a couple; it subsequently transpired that they had no biological relationship with the child. In its judgment of 27 January 2015, the Court’s Second Section found a violation of ECHR Article 8 (right to respect for private and family life), “in particular that the public-policy considerations underlying Italian authorities’ decisions – finding that the applicants had attempted to circumvent the prohibition in Italy on using surrogacy arrangements and the rules governing international adoption – could not take precedence over the best interests of the child, in spite of the absence of any biological relationship and the short period during which the applicants had cared for him. Reiterating that the removal of a child from the family setting was an extreme measure that could be justified only in the event of immediate danger to that child, the Court considered that, in the present case, the conditions justifying a removal had not been met. However, the Court’s conclusions were not to be understood as obliging the Italian State to return the child to the applicants, as he had undoubtedly developed emotional ties with the foster family with whom he had been living since 2013.” (From the Court’s Press Release.) The case was referred to the Grand Chamber, which on 24 January held, by by 11 votes to 6, that Article 8 had not been violated in this case. The short duration of the applicants’ relationship with the child and the uncertainty of the ties between them from a legal perspective meant that the conditions of family life had not been met. The right to respect for private life would be in violation of Article 8 if the actions of the Minors Court was contrary to law. According to Italian law the child was of unknown parentage and nationality and therefore in a state of abandonment within the meaning of the Adoption Act. In addition, Italian law prohibits “heterologous artificial reproduction”. These actions by the applicants severed any contractual relationship between the parents and the child. The Court held that the interference with the applicant’s private life was in accordance to the law.

Lupeni Greek Catholic Parish and Others v. Romania (no. 76943/11) – Grand Chamber Judgment 29 November 2016. The applicants’ requested restitution of a place of worship that had belonged to the Greek Catholic Church and was transferred during the totalitarian regime in Romania to the ownership of the Orthodox Church. The claim was dismissed by the Romanian courts, and the property was not returned. The Court found a violation of Article 6 § 1 in a breach of the principle of legal certainty and the length of the proceedings and ordered restitution in respect of non-pecuniary damage and expenses. (See comment by Frank Cranmer at Law & Religion UK.)

İzzettin Doğan and Others v. Turkey (no. 62649/10) – Grand Chamber Judgment 26 April 2016. The Turkish state discriminates against members of the Alavite branch of Islam by not providing public Alevite religious services, when services are provided for the majority Sunni population.

F.G. v. Sweden (no. 43611/11 – Grand Chamber Judgment 23 March 2016. Swedish authorities must assess the consequences of an Iranian national’s conversion to Christianity before deciding on his removal to Iran.

Parrillo v. Italy (no. 46470/11) – Grand Chamber Judgment 27 August 2015. Banning a woman from donating embryos obtained from in vitro fertilisation to scientific research was not contrary to respect for her private life.

Lambert and Others v. France (no. 46043/14) – Grand Chamber Judgment 5 June 2015 (rectified 26 June 2015). The case concerned the judgment delivered by the French Conseil d’État authorizing the withdrawal of the artificial nutrition and hydration of Vincent Lambert. Finding no consensus among the Council of Europe member states permitting the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, the Court concluded that States must be afforded a margin of appreciation. The legislative framework laid down by domestic law, as interpreted by the Conseil d’État, and the decision-making process, which had been conducted in meticulous fashion, was compatible with the requirements of Article 2. The Court therefore held, by a majority, that there would be no violation of ECHR Article 2 (right to life) in the event of implementation of the Conseil d’État judgment.

On 16 June the Court delivered its Grand Chamber judgments in the first cases concerning the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh. There are currently more than one thousand individual applications pending before the Court which were lodged by persons displaced during the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh. The first two cases are these:

Chiragov and Others v. Armenia (no. 13216/05) – Grand Chamber Judgment 16 June 2015.

Sargsyan v. Azerbaijan (no. 40167/06) – Grand Chamber Judgment 16 June 2015.

Hämäläinen v. Finland (no. 37359/09) – Grand Chamber Judgment 16 July 2014. The Court upheld a 2012 Fourth Section judgment regarding civil unions. The applicant is a Finnish national who underwent male-to-female gender reassignment surgery in 2009. Having previously changed her first names, she wished to obtain a new identity number that would indicate her female gender in her official documents. However, in order to do so her marriage to a woman would have had to be turned into a civil partnership, which she refused to accept. She complained under Articles 8, 12, and 14. However, the Grand Chamber agreed that there had been no violation of the applicant’s rights.

S.A.S. v. France (no. 43835/11) – Grand Chamber Judgment 1 July 2014. The Court upheld a 2011 ban by France on full-face veils in public. The applicant, a French national and Muslim woman, complained that the law violated her rights under Articles 8 (right to respect for private and family life), 9 (freedom of thought, conscience, and religion), and 10 (freedom of expression), as well as Article 14 (prohibition of discrimination). The Court found that “respect for the minimum set of values of an open democratic society,” specifically the minimum requirements for “living together,” outweighed the individual’s choice to wear a full-face veil. By “raising a veil concealing the face” an individual could violate the “right of others to live in a space of socialisation which made living together easier.” Furthermore, the Court pointed out that while the ban disproportionately affected Muslim women wishing to wear a full-face veil, there was nothing in the law which expressly focused on religious clothing; the ban also prevented any item of clothing which covers the face. For more information, please consult the Court’s press releases in English or French.

Fernández Martínez v. Spain (no. 56030/07) – Grand Chamber Judgment 12 June 2014. The case concerned the non-renewal of the contract of a married priest and father of five who taught Catholic religion and ethics, after he had been granted dispensation from celibacy and following an event at which he had publicly displayed his active commitment to a movement opposing Church doctrine. The Court held that there had been no violation of the Convention and considered that it was not unreasonable for the Church to expect particular loyalty of religious education teachers, since they could be regarded as its representatives. Press release title: The decision not to renew the contract, as religious education teacher, of a Catholic priest who was married and had several children, after his active involvement in a movement opposing Church doctrine had been made public, was legitimate and proportionate. [Judgment] [Press Release] [Legal Summary (3rd Section)]

O’Keefe v. Ireland (no. 35810/09) – Grand Chamber Judgment 28 January 2014. The case concerned the question of the responsibility of the State for the sexual abuse of a schoolgirl, aged nine, by a lay teacher in an Irish National School in 1973. By a decision of the Grand Chamber on 28 January 2014, the Court held by 11 votes to 6, that there had been a violation of Article 3 (prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment) and of Article 13 (right to an effective remedy) of the European Convention on Human Rights concerning the Irish State’s failure to protect the applicant from sexual abuse and her inability to obtain recognition at national level of that failure; and unanimously, that there had been no violation of Article 3 ECHR as regards the investigation into the complaints of sexual abuse at the school.

[See the Court’s Press Release:] The Court that it was an inherent obligation of a Government to protect children from ill-treatment, especially in a primary education context. That obligation had not been met when the Irish State, which had to have been aware of the sexual abuse of children by adults prior to the 1970s through, among other things, its prosecution of such crimes at a significant rate, nevertheless continued to entrust the management of the primary education of the vast majority of young Irish children to National Schools (State-funded primary schools privately managed under religious patronage), without putting in place any mechanism of effective State control against the risks of such abuse occurring. On the contrary, potential complainants had been directed away from the State authorities and towards the managers (generally the local priest) of the National Schools. Indeed, any system of detection and reporting of abuse which allowed over 400 incidents of abuse to occur in the applicant’s school for such a long time had to be considered ineffective.

Chiragov and Others v Armenia (no. 13216/05) – Grand Chamber hearing 22 January 2014. {Webcast of the hearing.} Applicants are Azerbaijani Kurds who were victims of the early 1990s conflict in the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (“the NKAO”). They were residents of the district of Lachin, where their ancestors had lived for hundreds of years. They were forced to flee their homes in 1992 and have since been unable to return to their homes and properties because of Armenian occupation. They complain under Article 1, Protocol 1 of interference with the right to peaceful enjoyment of their possessions. They further complain, under Article 8, of infringement of the right to respect for their private and family life, under Article 13 of lack of effective remedy, and under Article 14 of discrimination on the basic of ethnic and religious affiliation. After relinquishment of jurisdiction to the Grand Chamber on 9 March 2010, the Court held a hearing in this case on 15 September 2010. On 14 December 2011, the Grand Chamber declared the application admissible. The Grand Chamber held a hearing in the case on 22 January 2014.