CELEBRATING THE CENTER’S 20TH ANNIVERSARY

INTRODUCTION

By ICLRS Director Brett Scharffs

The Center was officially launched on January 1, 2000: the dawn of a new millennium, a beginning with obvious symbolic significance, as well as a date that makes it easy for us to remember how long we’ve been in business. Over the two and a half decades that we have held the annual International Law and Religion Symposium, we have welcomed more than 1200 delegates. The theme we’ve adopted at the Center this year, Field Makers, provides an opportunity to reflect on the growth of the field of international and comparative law and religion studies over the past 20 years and also to reflect upon our efforts individually and collectively to contribute to this field of study.

I had only been at the law school for three years when the International Center for Law and Religion Studies was founded. Care was given to the creation of our mission statement, which speaks of helping secure the blessings of freedom of religion and belief for all people in all places in three specific ways: by expanding, deepening and disseminating knowledge and expertise; by facilitating the growth of networks of scholars, experts and policymakers; and by contributing to law reform processes. Twenty years later, we can pause and assess our progress.

Click on an infographic to view full size.

HISTORY OF THE CENTER

In the 1980s and ’90s, the field of law and religion was relatively small and primarily focused on the United States. But W. Cole Durham Jr.—a Harvard law graduate, a BYU Law professor, and the recently elected secretary of the American Associate of Comparative Law—was in the right place at the right time. In the months prior to the collapse of the Berlin Wall, Durham recognized the magnitude of the changes that such an event would entail. He arranged visits to various capitals in Central and Eastern Europe, and he was in Berlin as the wall fell. Durham soon found himself consulting on law reform and constitution making throughout Eastern Europe, organizing comparative law conferences, and weaving together a network of experts with the purpose of sharing ideas, collaborating, and contributing to publications.

Recognizing the need to establish an institutional base to give greater support to his work, Durham launched the International Center for Law and Religion Studies (the Center) within the BYU Law School on January 1, 2000. The Center proclaims the mission “to help secure the blessings of freedom of religion and belief for all people.”

The Center started out with Founding Director W. Cole Durham, Jr., and Associate Director Elizabeth A. Clark (both pictured in Center).

The Center started with only two people: Durham as director and Elizabeth Clark as associate director. Now retired from teaching, Durham serves as founding director, with BYU Law professor Brett G. Scharffs as director. The Center relies on five associate directors to lead the work in various regions of the world with the support of volunteer senior fellows and additional staff members. While the Center itself maintains a small footprint, its reach continues to expand as it develops the field of law and religion.

“The kind of impact you can have worldwide when you really are committed to the field…is just phenomenal,” says Clark. “Religious freedom is too big a topic for us to do it all…We can lift people from different faith traditions and different countries interested in this field and give them opportunities.”

The Center’s signature event is the Annual International Law and Religion Symposium. Now in its 28th year, the conference has grown from a small event put together “with Scotch tape and bobby pins,” according to Durham, to the premier event of its kind. To date, some 1,400 people from 125 countries have participated in the symposium, including world religious leaders; leading officials dealing with religious freedom from the UN, the EU, and the US; and academic, government, media, and civil society leaders from across the globe.

The Annual International Law and Religion Symposium draws delegates from around the world for the premier scholarship event on law and religion.

Additionally, the Center co-organizes law and religion conferences annually in eight regions of the world. By replicating the symposium’s structure for these conferences, the Center has broadened its reach and helped to develop worldwide consortia of scholars, government leaders, and religious leaders engaged in law and religion.

“The Center has been extraordinarily successful in helping people who share our interest in religious freedom have an avenue to advance those topics in their own countries. In short, all they really need is a forum,” says associate director Gary Doxey. “When we can get…people to take the lead in law reform in their own countries, that’s when you really make a difference.”

Known as “the casebook,” this book by W. Cole Durham, Jr., and Brett G. Scharffs is used all over the world as the premier text on law and religion.

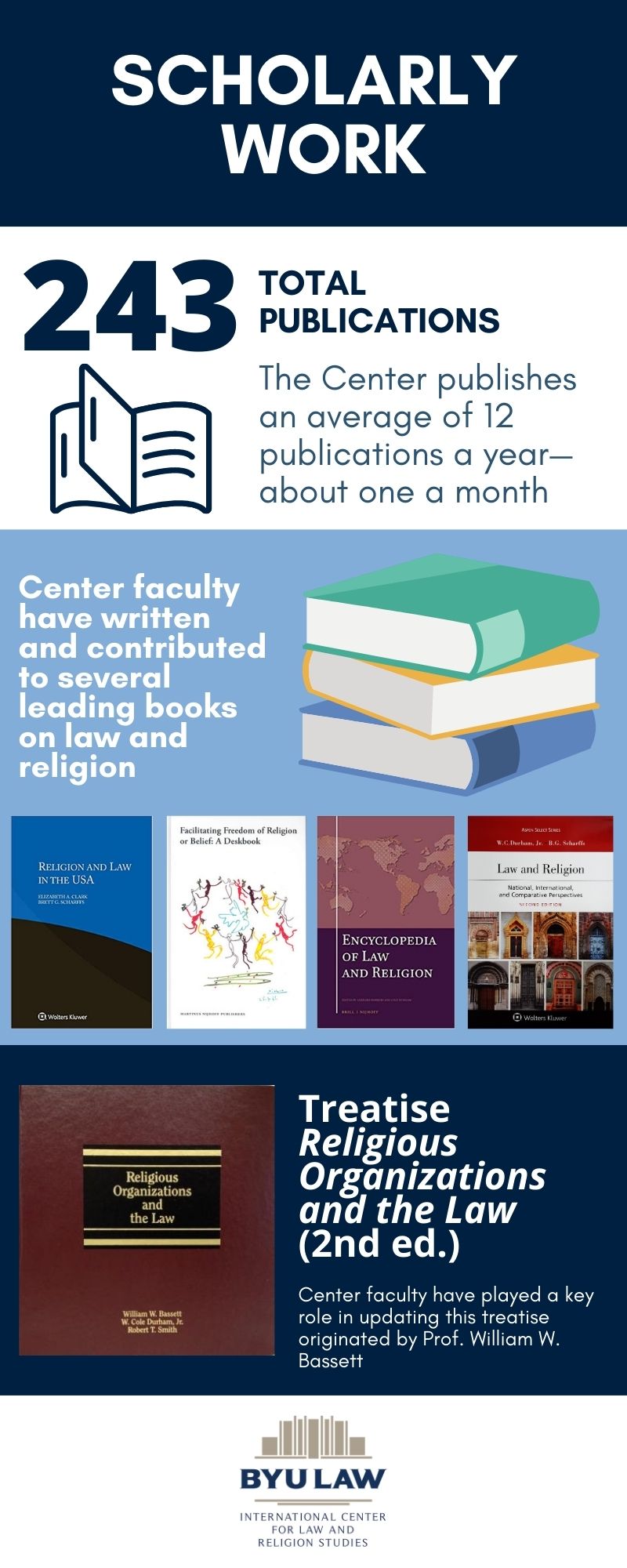

Scholarship has also grown over the years. The Center is responsible for several first-of-its-kind publications on law and religion. One such publication is known fondly as “the casebook.” Titled Law and Religion: National, International, and Comparative Perspectives, it represents both US and international law perspectives and incorporates comparative constitutional law. It has been translated or is in the process of being translated into 12 languages and is used in multiweek certificate training programs on religion and the rule of law sponsored by leading academic and legal bodies in China, Vietnam, Myanmar, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Oxford, UK.

These efforts only scratch the surface of 20-plus years of “field-making.” The Center is involved in 30 to 50 other events each year as a participant, cosponsor, or co-organizer. Staff members contribute to law reform projects around the world. And in December 2018, the Center was a key player in the Punta del Este Declaration on Human Dignity for Everyone Everywhere. There is still much to be done as the field of law and religion changes and the world evolves, and the Center remains committed to its mission “to help secure the blessings of freedom of religion and belief for all people.” “What does it mean to be human?” asks Clark. “It means caring about the deepest things that people care about in their lives, about their relationship to God or to the universe or to meaning. These all intersect when you look at questions of law and religion. They are never going to be completely resolved because they are at the core of culture and history and identity. And that’s what makes them fascinating and why it’s so important to do our best work.”